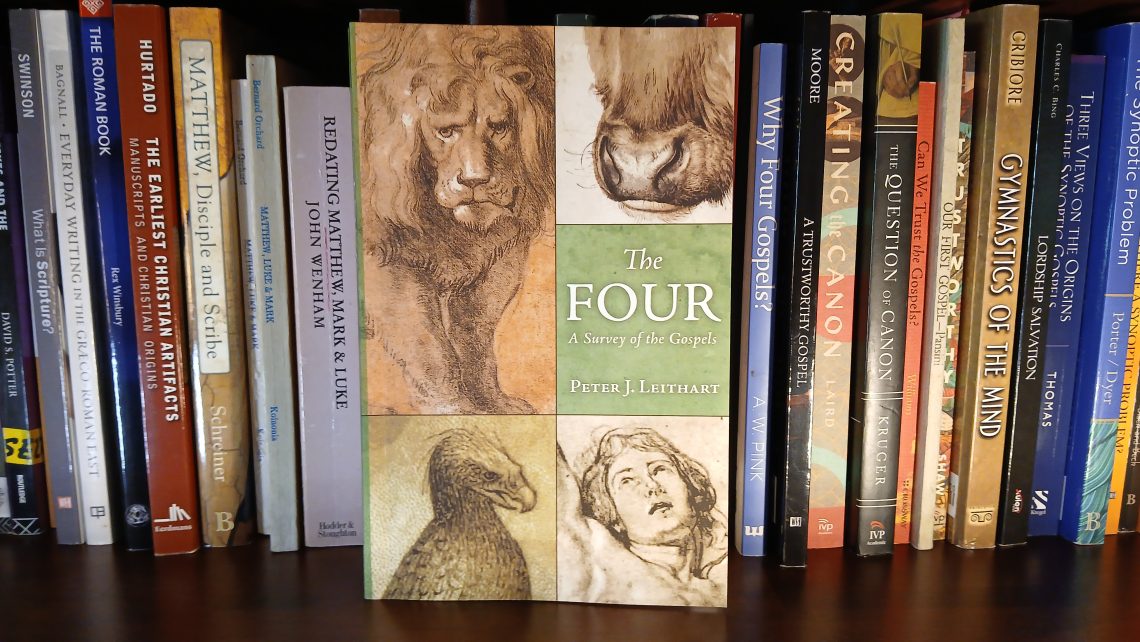

The Four: A Survey of the Gospels. By Peter J. Leithart. Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2010, 251 pp.

In chapter 3 of his Survey of the Gospels, Peter Leithart introduces three questions which arise because of the similarities and differences between Matthew, Mark, and Luke: “Where do the Gospels come from? Which Gospel comes first? Do any of the evangelists [Gospel authors] use the writings of other evangelists?” (95). Beyond this material on the synoptic problem, the book also offers insightful comparisons between the four Gospels.

Imagine my pleasure in discovering that our views align on much concerning the origins of Matthew.

Leithart dismisses the popular modern theory that Mark was the first Gospel published, perhaps alongside a document commonly called Quelle (Q). Leithart retorts:

Let’s suppose that the Gospels are what they say they are, and what the early church believed they were: Eyewitness accounts of the life of Jesus, or books based on eyewitness accounts. For the church fathers, Matthew writes the first gospel. He is one of The Twelve and therefore writes down things he himself saw and words he himself heard. Being a tax collector, Matthew can read and write. Even during Jesus’ life, Matthew may have written down things Jesus says and does. A few days after the sermon on the mount, we can imagine, copies of Matthew’s “sermon notes” begin circulating among Jesus’ followers (99–100).

With regard to the dating of the Gospels, Leithart gets to the heart of the concern over theorized late dates; a concern which I share:

Consider: If the Gospels are written shortly after Jesus dies and rises again, by eyewitnesses, are you inclined to believe them? What if they are written fifty years after Jesus, by people who never knew Jesus Himself? Are you as likely to believe the Gospels then? The further away the Gospels are from the events of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, the less reliable they seem (102).

In my book, A Trustworthy Gospel: Arguments for an Early Date for Matthew’s Gospel, I demonstrate that the ancients were concerned about the reliability of aging memories, even as we are.

Leithart goes on to cite John Wenham’s conclusion that Matthew wrote “around AD 40, Mark around AD 45, Luke around 54, and Acts around 62” (103). But then, Leithart declares his preference for an even earlier date for Matthew:

But I suspect that the gospels are written even earlier than Wenham thinks. I don’t see any reason why Matthew could not have written his Gospel in the 30s. For millennia Jews were people of the book: All the major events of Israel’s history were written, and those written accounts were the basis of Israel’s entire national life. … Are we to believe that now that the climactic event of Israel’s history has occurred, they decided to wait several decades to write it all done? What reason do they have for waiting at all? (107)

I’ve focused here on what Leithart has to say about Matthew, but Leithart also addresses Mark’s publication date and his use of portions of Matthew, as Mark composes a Gospel based on the teachings of Peter, as reported by Christians after the apostolic age.

Bottom-line is that it is great to have found another modern scholar who affirms an early Matthew.

NOTE: Comments and dialog are welcome. The “Leave a Reply” field will be accessible below for 10 days after this post was published. Afterwards, please feel free to continue to comment via the contact page. (This is my attempt to manage the spam bots.)