The Gospel of Mark offers Greek translations for a variety of transliterated Aramaic words. What does this tell us about Mark’s intended audience? Many scholars claim that Mark’s translations demonstrate that his audience was not familiar with Aramaic. However, if we look closely at how both Mark and Matthew handle the particular words involved, particularly if we assume Matthean priority, then I suggest that Mark’s translations actually indicate that Mark’s original audience, though primarily Greek speaking, actually did have a limited familiarity with Aramaic, which suggests that the original audience was located in a region where the language was spoken, such as Caesarea Maritima.

This article (1) begins by surveying various scholars who make the “not familiar with Aramaic” claim, then (2) surveys Mark’s Aramaic translation passages along with the parallel passages in Matthew, and finally, (3) argues that Mark’s original audience was expected to have some familiarity with Aramaic.

PERSPECTIVES ON MARK’S TRANSLATIONS

Here are excerpts from various scholars who make the claim that Mark’s translations demonstrate that his audience was not familiar with Aramaic.

The need to translate Aramaic terms into Greek for his readers, as Mark does on several occasions, also suggests that he wrote in an area where Aramaic was not familiar.1 (France, Mark, NIGTC, 2002, 41)

There can be little doubt that Mark wrote for Gentile readers, and Roman Gentiles in particular. Mark quotes relatively infrequently from the OT, and he explains Jewish customs unfamiliar to his readers … He translates Aramaic and Hebrew phrases by their Greek equivalents. … He also incorporates a number of Latinisms by transliterating familiar Latin expressions into Greek characters.2 … These data indicate that Mark wrote for Greek readers whose primary frame of reference was the Roman Empire, whose native tongue was evidently Latin, and for whom the land and Jewish ethos of Jesus were unfamiliar. Again, Rome looks to be the place in which and for which the Second Gospel was composed.3 (Edwards, Mark, PNTC, 2002, 10)

Mark translates Aramaic words into Greek for his readers … which appears to rule out a Palestinian (or Syrian?) audience.4 (Strauss, Mark, ZECNT, 2014, 34)

Another suggestion, that the gospel was written in Galilee … is at odds with Mark’s lack of geographical knowledge and his explanation of Aramaic terms. All we can say with certainty, therefore, is that the gospel was composed somewhere in the Roman Empire—a conclusion that scarcely narrows the field at all!5 (Hooker, Mark, BNTC, 1991, 7–8)

From within Mark we learn a great deal about the audience for whom it was written. We know it was a Greek-speaking audience that did not know Aramaic, as Mark’s explanations of Aramaic expressions indicate.6 (Stein, Mark, ECNT, 2008, 9)

Similar assertions are made by deSilva,7 Turner,8 Guthrie,9 Taylor,10 etc.

Alan Cole offers several interesting proposals that might support the above assertions, arguing that the Aramaic words were either “vivid Petrine memories” or else “unselfconscious reproduction of words which already were ‘fossilized’ in the Greek tradition as it came to Mark.”11 Alternatively, perhaps Mark “was not at the stage of sophistication where he would have felt it necessary to remove uncouth ‘foreign’ words.”12 As an illustration of fossilized words, Cole notes that certain “Hebrew and Aramaic words or phrases” have continued to be “embedded” in our modern Christian vocabulary, such as hallelujah, amen, and hosanna.13

MARK’S TRANSLATIONS AND THE PARALLEL PASSAGES IN MATTHEW

The Gospel of Mark, written in Greek, includes a variety of transliterated Aramaic words, along with their Greek equivalents, suggesting to many that Mark was written for an audience not intimate with the Aramaic terms.14 However, I suggest that, before one draws conclusions regarding Mark’s implied audience, one should first assess the specific passages alongside their Matthean parallels.

In the following instances where Mark uses an Aramaic word, Matthew has either (1) omitted the Aramaic word while providing the Greek equivalent; (2) omitted the word of interest; (3) or has altogether omitted the event.

- Mark 3:17. Jesus gives to James and John “the name Boanerges, that is, Sons of Thunder.” This detail is not included in Matthew 10:2.

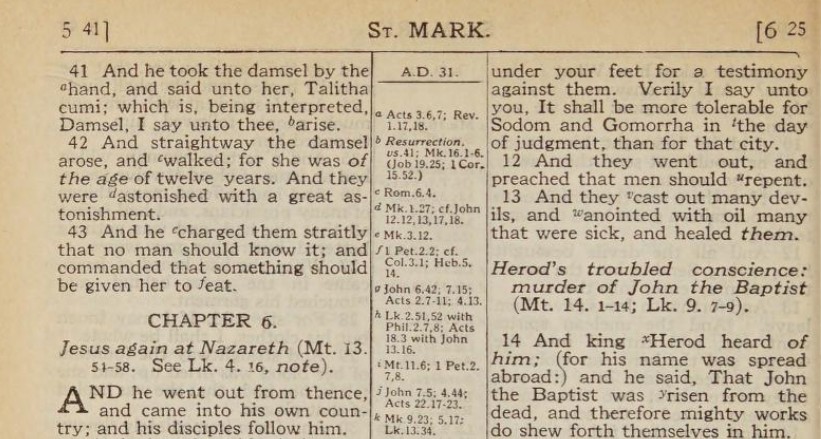

- Mark 5:41. Jesus speaks to the girl who has died, “‘Talitha cumi,’ which means, ‘Little girl, I say to you, arise’.” Matthew omits these words in his account (Matt 9:25).

- Mark 7:11. Jesus chastises the Pharisees for both their failure to comply with the law and their hypocrisy, in their practice of identifying certain things as “‘Corban‘ (that is, given to God),” such that the possessions can’t then be used to help their parents financially. In contrast, Matthew explains the practice without using the term: “But you say, ‘If anyone tells his father or his mother, ‘What you would have gained from me is given to God,’ he need not honor his father”” (Matt. 15:5 ESV).

- Mark 7:34. Jesus, as he cures a man’s deafness and speech impediment, says to him “‘Ephphatha,’ that is, ‘Be opened’.” Matthew omits the details of this and other healings (Matt. 15:29–31).

- Mark 10:46. Jesus, as he was leaving Jericho, came upon “Bartimaeus, a blind beggar, the son of Timaeus” and Jesus cures the blindness. Here, Mark is explaining the meaning of the man’s name. Matthew’s account omits the name (Matt. 20:30).

- Mark 14:36. In the garden of Gethsemane, Mark begins his prayer with, “Abba, Father,” whereas Matthew simply begins with “My Father” (Matt 26:39).

In a few instances, both Gospels offer the same translation. For example, Golgatha is translated as “Place of a Skull” in both Gospels (Mark 15:22; Matt 27:33), perhaps suggesting that this was a local place name that might not be familiar to either audience. Additionally, both Matthew and Mark provide Jesus’ final words on the cross in both transliterated Aramaic and Greek (Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34), presumably because of the significance of these final words.

MARK’S ORIGINAL AUDIENCE

What do these Aramaic to Greek translations tell us about Mark’s audience? First, let’s accept the testimony of the church fathers that Mark’s Gospel was written at the request of those who wanted a record of Peter’s preaching (e.g., Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.1.1; Clement per Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.14.6). Second, let’s accept that certain words and phrases were adopted into the early Christian culture, as suggested by Cole. However, this neither proves nor disproves the assertion that Aramaic was or was not otherwise familiar to Mark’s original audience.

On the popular theory that Mark was the first Gospel, then Alan Cole’s first proposition might be appealing, that Mark was simply retaining the vividness of Peter’s storytelling by including the occasional Aramaic word. And yet, if this reflects Peter’s storytelling in Rome, thirty years after the resurrection as is commonly asserted, then one must wonder whether Peter would still be inserting foreign words into a sermon for an audience unfamiliar with such. Would one speaking to an English-speaking audience randomly insert words in Japanese or Egyptian? Perhaps this proposition, rather than being applicable to the ancients, instead reflects the familiarity and reverence that biblical scholars have for biblical languages.

Or even if Peter did slip in random foreign words, what obligation would Mark have had to retain such? Are we to accept that Mark, the one who had traveled with apostles and had edited together a Gospel-length piece of literature, was unsophisticated, per Cole?

The fossilized word theory is intriguing. However, if Mark was indeed the first Gospel, then why do the other Gospels not echo more of Mark’s Aramaic terms? Further, if there was widespread embrace of fossilized Aramaic words within Christian culture, then why do we not find more examples of such in the rest of the NT? In Paul’s writings, we have Abba (Rom. 8:15; Gal. 4:6) and Maranantha (1 Cor. 16:22). Where are the other examples? The bottom-line is that it is hard to accept either Cole’s propositions or the generic claim that the transliterations and translations demonstrate that the audience did not know Aramaic.

If, in contrast, we work on the premise that Matthew was the first Gospel, followed by Mark, then one must then explain why Mark would add the Aramaic words that Matthew had omitted. As I envision Matthew, it was published as Peter and Paul began preaching to those outside of the land of the Jews, coincident with the events of Acts 10–11.15 However, its intended audience had in view “Jews, devout men from every nation,” as had been present at Pentecost (Acts 2:5).

Again, if Matthew was written with only a few significant transliterated Aramaic words, then why would Mark insert more Aramaic? At this point, it appears that the only viable theory is that Mark expected his original audience to have at least some familiarity with the Aramaic words, even though Aramaic was not their primary language. This suggest that the intended audience was composed of Greek-speaking non-Jews, who were located in a region where Aramaic was spoken, such as Caesarea Maritima.

Other suggestions?

- France makes this statement with a footnote to a work by Chapman. It is not clear in the subsequent paragraph whether France affirms the assertion or not. R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek Text, New International Greek Testament Commentary (Eerdmans, 2002), 41, 41n89; Dean W. Chapman, The Orphan Gospel (JSOT Press, 1993), 29. ↩︎

- Note that I’ve already argued that Latin loan words do not demonstrate a Greco-Roman audience for Mark, any more than it does for Matthew. ↩︎

- James R. Edwards, The Gospel According to Mark, Pillar New Testament Commentary (Eerdmans, 2002), 10. ↩︎

- Mark L Strauss, Mark, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Zondervan, 2014), 34. ↩︎

- Morna D. Hooker, The Gospel According to Saint Mark (Continuum, 1991), 7–8. ↩︎

- Robert H. Stein, Mark, Baker Exegetical Commentary of the New Testament (Baker Academic, 2008), 9. ↩︎

- David A. deSilva, An Introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, Methods and Ministry Formation (InterVarsity, 2004), 196. ↩︎

- David L. Turner, Interpreting the Gospels and Acts: An Exegetical Handbook (Kregel Academic, 2019), 99. ↩︎

- Donald Guthrie, New Testament Introduction, 3rd (revised) (InterVarsity, 1970), 59–60. ↩︎

- Vincent Taylor, The Gospel According to Mark (MacMillan, 1959), 32. ↩︎

- R. Alan Cole, Mark: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (InterVarsity, 1989), 59–60. Barclay suggests that the Aramaic terms were included because “there were times when Peter could hear again the very sound of Jesus’ voice and could not help passing it on to Mark in the very words that Jesus spoke.” William Barclay, The Gospel of Mark, The New Daily Study Bible (Saint Andrew Press, 2001), 9–10. ↩︎

- Cole, Mark, 59–60. Blomberg also leans on the “highest incidence of Aramaic words preserved in Greek transliteration” as another argument for Markan priority, evidently on the premise that this primitiveness was subsequently removed by the more refined Gospels. Craig L. Blomberg, Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey (Broadman & Holman, 1997), 89. ↩︎

- Cole, Mark, 59–60. There is merit to this illustration from Cole, as it may explain Paul’s use of “Abba, father” in Romans 8:15. (See I. Howard Marshall, Biblical Inspiration (Paternoster, 1982), 79). However, if Mark retained Aramaic terms primarily due to their integration into the Christian psyche, then why would subsequent Gospel authors fail to include such? ↩︎

- See Strauss for a helpful list of verses containing translated Aramaic words. Strauss, Mark, 34. ↩︎

- Irenaeus’ “at Rome” affirms an early Matthew! ↩︎

NOTE: Comments and dialog are welcome. The “Leave a Reply” field will be accessible below for 10 days after this post was published. Afterwards, please feel free to continue to comment via the contact page. (This is my attempt to manage the spam bots.)