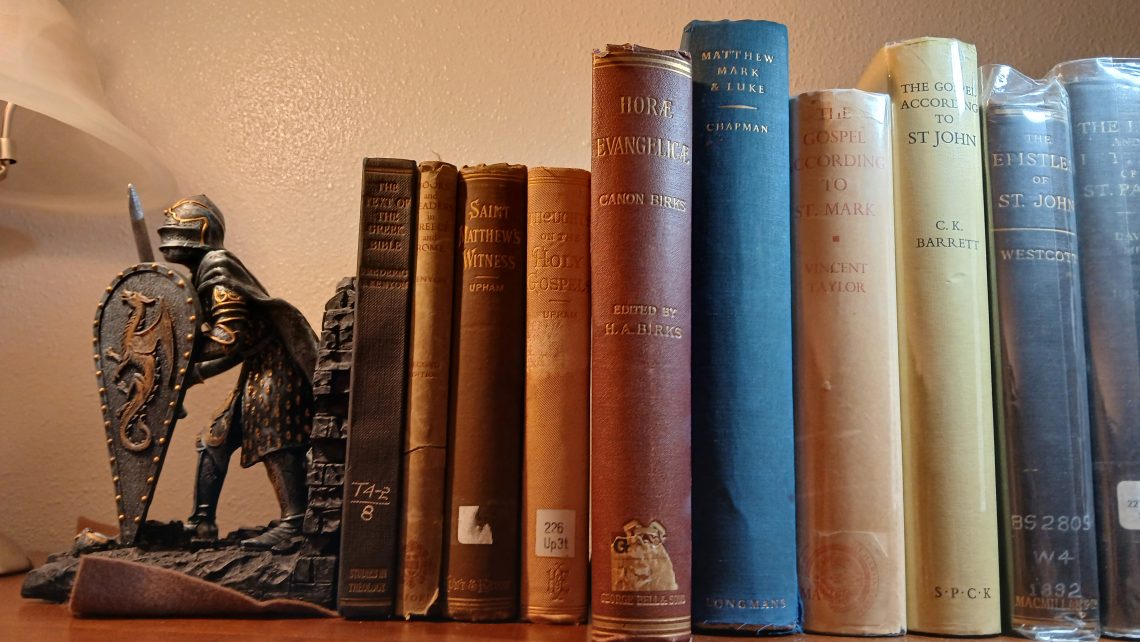

Thomas Birks’ 1852 book, Horæ Evangelicæ, encourages us to seriously consider much earlier dates for the Gospels than is presently popular. In Birks’ day, liberal German theologians (e.g., David Strauss) were characterizing the Gospels—”not as real histories, but as a collection of early legends that had their origin in ideal conceptions of the Messiah, which gradually assumed a definite form. … [having] a date very considerably removed from the events they profess to record.”1 Speculations were being advanced that the Gospels were composed thirty, sixty, or more years after the crucifixion, and this “mythical theory” allowed for suspicions that “facts and legends” had been “confounded together.”2 Even those theologians rejecting these propositions as a whole were allowing for “errors and inconsistencies in the Gospels.”3 These challenges to the integrity of the Gospels persist even today.

Accordingly, Birks conducted his own assessment of the Synoptic Gospels with regard to their dates, provenance, consistency, structure, design, etc. With respect to dates and provenance, his conclusion was that Matthew “was written only twelve or fourteen years after the ascension.”4 The Gospel of Mark was written, “not at Rome, but at Caesarea, a few years later; and that of St. Luke, still a few years later, or about AD 52, in the neighborhood of Antioch.”5 Birks recognized the apologetic benefit to this approach: “If the reasoning is just, it is needless to remark the strong proof, which is thus afforded to the church, of their apostolic authority.”6 While I would date these Gospels even a few years earlier, I am intrigued by his efforts.

In this article, we will survey several highlights from his text, but with a primary interest in his proposed dates and provenance for the Synoptic Gospels.

PART I. ON THE MUTUAL RELATION OF THE FOUR GOSPELS.

In the first major part of the book, Birks argues that each Gospel author had access to prior Gospels, that the Gospels were composed in Matthew-Mark-Luke order, that Luke’s chronology is to be preferred, etc. Birks then proceeds to compare and contrast the four Gospels over the course of several chapters. These are important topics, but our immediate interest is more narrow. Nonetheless, this mid-section summary is helpful:

The principle, then, that each later Evangelist knew the writings of his predecessors, will by no means imply, as some have hastily assumed that he would become a mere copyist, even in the parts common to both writers. Each of them was an original authority, possessed of independent information, and

might either use it independently, or combine it with the previous accounts, according to the plan and object of his own work. We may assume, as certain, that each later gospel would have a double purpose; to furnish a new testimony of facts already on record, or to communicate new facts and discourses, and place those in a new light, which had been previously given. The former object would require that many particulars should be the same; and the latter, that many should be different.7

PART II. INTRODUCTION. ON THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE GOSPELS.

The second major part of the book is concerned with establishing the date of Acts and the events therein, followed by assessments of the Gospels. Birks assigns the crucifixion to AD 30, conversion of Paul to AD 37, conversion of Cornelius to AD 41, beginning of the 1st Missionary Journey to AD 45, the Jerusalem council to AD 50, beginning of the 2nd MJ to AD 51, 3rd MJ to AD 54, and so on.8 The “unfinished air” which concludes the narrative in Acts leads Birks to believe that Acts was completed shortly after the final events of the account.9 However, Birks contends that all but the last two chapters were composed during Paul’s imprisonment at Caesarea Maritima, “and only the conclusion added at Rome.”10 This Caesarean provenance provided convenient access to those who could provide historical details. In sum, Birks asserts that Acts was published in AD 63.11

Birks then argues that Theophilus, the believing Gentile recipient of Acts (per Acts 1:1), was located in Antioch. This determination will subsequently play into the proposed provenance of the Gospel of Luke. Theophilus was a person of rank who “was not a resident in Palestine and had not even visited Jerusalem.” This is demonstrated by the apparent need to explain that Capernaum was in Galilee per Luke 4:31, the need to explain that Mount Olivet was near Jerusalem per Acts 1:12, etc.12 Yet, Theophilus was expected to have a general “acquaintance with the geography.”13 Nor was he familiar with the activities at the Aeropagus in Athens (Acts 17:21), nor “well acquainted with Macedonia (16:12),” nor with Corinth or Ephesus.14 Ultimately, Birks also dismisses Italy as the possible residence of Theophilus, in favor of somewhere in Syria or Asia Minor, given the interest in local political figures such as Quirinius, references to Greek coins, familiarity with regional place-names (e.g., Cyprus, Antioch, Seleucia, Caesarea), etc.15 Birks settles on Antioch, largely because of the significance of Antioch to Acts and the minimal details offered regarding the city, the church, evangelistic activities, sermons preached there, etc.16 Birks also subsequently proposes that the author, Luke, was also “a native or a resident” of the city.17

Birks attention then turns to the period of time separating the publication of Luke and Acts, on the premise that they were both composed by Luke. Contrary to some scholars, Birks argues that there are indications within these texts that a substantial time had transpired.18 Furthermore, Birks points to the passage which speaks of the ‘brother who is famous in the gospel’ (2 Cor. 7:18) as referring to Luke and his Gospel.19 Next, Birks surveys Luke’s travels with Paul and proposes that, before Luke joined Paul in Troas on the 2nd journey (Acts 16:10-16), Luke had composed his Gospel in Antioch.20 Hence, the Gospel of Luke was composed around AD 51–52.21 Bringing the Gospel with him, Luke joined Paul briefly before settling in the major city of Philippi, as his base for distributing his Gospel “to the churches of Macedonia and Greece.”22

Next, Birks considers the Gospel of Mark. He rejects claims that the Latinisms in Mark imply a Roman provenance, noting the frequency of Latinisms that are also found in the other Gospels.23 Instead, implications that geographic locations were known already [by the audience] and the assumption of “a general acquaintance with the customs of the Jews,” both indicate “that it [the Gospel] was addressed to residents in Palestine.”24

Early church history, as presented in Acts, is naturally divided into three periods, with the initial spread of the gospel among the Jews, the early spread of the gospel among Gentiles (up to the time of the Jerusalem council), and the subsequent rapid spread of the gospel throughout the known world.25 Accordingly, Mark fits well into the second period, serving those such as Cornelius in Caesarea. Notably, on the premise that Mark was “written at Caesarea, or for the Roman converts in that place, [at] about AD 48, it [Mark] would probably be soon carried to Rome.”26 This scenario might explain the tradition that Mark was written in Rome, according to Birks.27

Backing up further, Birks asserts that Matthew was written in the first period of Acts in or near Jerusalem, around AD 42, to serve the needs of Jewish believers.28 According to Birks, this was spurred on by the “conversion of Cornelius and the call of the Gentiles.”29 Birks discounts Irenaeus’ testimony concerning the origins of Matthew, given Irenaeus’ assertion that Mark was published after the death of Peter and Paul.30 [However, many scholars have countered that this “after the death” translation of Irenaeus is not valid.] Birks also dismisses the tradition that Matthew was originally written in Hebrew.31 Overall, he offers a number of arguments in support of an early Matthew that are of varying quality. Perhaps most useful are his observations concerning (1) the identification of “several minute allusions in the Gospel” to “local circumstances and incidents of our Lord’s personal ministry”; (2) allusions to individuals with whom readers were expected to be familiar; and (3) the Jewishness of the Gospel, with its “frequent quotations from the prophets.32

PART III. INTRODUCTION. THE HISTORIC REALITY OF THE GOSPELS.

This next portion of Birks treatise is beyond the scope of our immediate interest. However, he does helpfully defend the integrity of the Gospels on the basis of not only “undesigned coincidences”—as had been argued by several contemporaries and more recently by Lydia McGrew—but also on the basis of “reconcileable diversity.”33

PART IV. ON THE IDEALITY OF THE GOSPELS.

This final section explores the nature of the Gospels, as being higher and nobler, and as divine revelation.34

SUMMARY

There is much to appreciate in Birks’ work. I highly recommend it to those who are open to considering early dates. Per Birks, Matthew was published around AD 42 in or near Jerusalem, Mark in AD 48 in or for those in Caesarea Maritima, and Luke in AD 51–52 in Antioch. His arguments are of various quality—some are well-grounded and some are more circumstantial, subjective, and even reversible. On the whole though , he offers a perspective which I affirm as correctly positioning the publication of the Synoptic Gospels in alignment with the phased expansion of the Christian church. That said, I am resolved that Matthew and Mark were published a few years earlier than Birks argues. I am also intrigued by the proposed date and provenance of Luke; yet need to ruminate on such further. Phil Fernandes, in his “Redating the Gospels” (which largely echoes John Wenham) suggests publication dates of AD 35–42 for Matthew, as early as AD 45 for Mark, and AD 45–50 for Luke.35 I believe that these are in the ballpark.

David Alan Black, in his Why Four Gospels? (echoing Bernard Orchard), offers a similar publication paradigm, where Gospels are said to be published coincident with the phased expansion of the church. His treatise is also worthy of consideration; although, Black and Orchard defer Mark to a later “Roman Phase” in the AD 60s.36 This late date and his Matthew-Luke-Mark publication sequence is in deference to Clement of Alexandria’s testimony that the Gospels “containing the genealogies” were published first.37 In contrast, I continue to preference Irenaeus’ testimony on publication order, once we resolve some of his difficult statements, as I have attempted in A Trustworthy Gospel.38

Before we conclude, I want to recommend two additional resources, with which Birks frequently interacts. First is Thomas Townson’s Discourses on the Four Gospels.39 Second is Edward Greswell’s Dissertations upon the Principles and Arrangement of an Harmony of the Gospels. While Birks differed with Greswell in some areas, he found the work to overall be valuable.40

- Thomas R. Birks, Horae Evangelicae: The Internal Evidence of the Gospel History (George Bell & Sons, 1852), 1. ↩︎

- Ibid., 2–3. ↩︎

- Ibid., 2. ↩︎

- Ibid., vii. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., 61. ↩︎

- Ibid., 182–83. ↩︎

- Ibid., 187. ↩︎

- Ibid., 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., 200. ↩︎

- Ibid., 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., 192. ↩︎

- Ibid., 189. ↩︎

- Ibid., 189–91, 213–14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 193. ↩︎

- Ibid., 199. ↩︎

- Ibid., 202–03. ↩︎

- Ibid., 204. ↩︎

- Ibid., 209. ↩︎

- In the preface, the date is given as about AD 52. Later, the date is given as about AD 51. Ibid. vii, 209. ↩︎

- Ibid., 210–11. ↩︎

- Ibid., 226. I have likewise pushed back against the Latinisms argument in “Latin loan words do not demonstrate a Greco-Roman audience for Mark.” ↩︎

- Ibid., 227–28. ↩︎

- Ibid., 229–30. ↩︎

- Ibid., 232. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., 242. ↩︎

- Ibid., 243. ↩︎

- Ibid., 243. I’ve previously addressed this elsewhere. ↩︎

- Ibid., 261–68. I’ve previously addressed this elsewhere. ↩︎

- Ibid., 252, 254–55. ↩︎

- Ibid., 269. ↩︎

- Ibid., 455. ↩︎

- Phil Fernandes, “Redating the Gospels,” in Vital Issues in the Inerrancy Debate, ed. F. David Farnell (Wipf and Stock, 2015), 488. ↩︎

- David Alan Black, Why Four Gospels?: The Historical Origins of the Gospels, 2nd ed. (Energion, 2010), 72–74. ↩︎

- Ibid., 31. ↩︎

- Daniel B. Moore, A Trustworthy Gospel: Arguments for an Early Date for Matthew’s Gospel (Wipf and Stock, 2024). ↩︎

- Thomas Townson, Discourses on the Four Gospels, Chiefly with Regard to the Peculiar Design of Each, and the Order and Places in Which They Were Written, 2nd ed. (Clarenson, 1788). ↩︎

- Edward Greswell, Dissertations upon the Principles and Arrangement of an Harmony of the Gospels, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Oxford University Press, 1837). ↩︎

NOTE: Comments and dialog are welcome. The “Leave a Reply” field will be accessible below for 10 days after this post was published. Afterwards, please feel free to continue to comment via the contact page. (This is my attempt to manage the spam bots.)